Social Exchange Theory (SET)

Social exchange theory explains the social behaviour in dyadic and collective relations by applying a principle of a cost-benefit analysis of relations.

Social Exchange Theory: A review

Introduction

Social Exchange Theory (SET) emerged at the end of the 1950s and has since developed into a large body of research on social behaviour. The theory has been widely used to explain both utilitarian and sociological views on relations within social networks (Blau, 2017; DeLamater & Ward, 2013; 1987; Homans, 1961). The emergence and the development of the theory were largely attributed to the works of John Thibaut, George Homans, Peter Blau and Harold Kelley. They were interested in the psychology of small groups, aiming to understand interpersonal relationships in communities and dyadic relationships (Emerson, 1976). Specifically, Homans used a reductionist approach to explain the relationships between people through reinforcement mechanisms, whereby the behaviour of social actors is reinforced by reward and inhibited by punishments (Delamater, 2006). The idea that the reinforcement mechanism underpins social relations stemmed from the research on operant conditioning (e.g. the works of Burrhus Frederic Skinner). That stream of research viewed behaviour as a result of a learning process through the positive and negative consequences that such behaviour entails. (Homans, 1961). Blau built the theory by offering a technical-economic perspective on the analysis of the properties of social systems (Blau, 2017). While he shared similar views on rewards and punishments, Blau’s research approach derived from the principles of utilitarianism. He considered the rationale for behaviour resulted from anticipation, rather than the perception of actual gains (DeLamater & Ward, 2013). Thibaut and Kelley applied theoretical concepts to human decision making in social groups and developed matrices to predict the outcomes of relations. The matrices represent different outcomes of exchange defined by the different proportions of costs and rewards that people receive/incur in interpersonal relations. An individual’s decision to continue or participate in exchange depends on the degree to which it brings better rewards (e.g. social power, profit) or higher economies in costs compared to other competing relations (Thibaut & Kelley, 2017). Although the approaches of the theory construction and analysis diverged among the four scholars, they shared the idea that behaviour in social groups is a form of exchange. The differences in the perspectives on the analysis of social relationships have defined the evolution of the social exchange research and the significant role that it played in the literature.

The emergence of SET brought together the sociological, economic and psychological perspectives, advancing research on human behaviour. This approach aimed to resolve debates in the literature about using economic approaches in anthropological research (Knight, 1940; Malinowski, 2013). Due to the heavy reliance on a rational interpretation of human decision making in the market context, the applicability of economic theories to normatively regulated behaviour had been questioned. Therefore, the development of the social exchange research enabled the application of a quasi-economic type of analysis to social systems. Also, the interdependence concept introduced by the SET aimed to contribute to sociological theories. Prior anthropological research viewed people as independent from the actions of other actors and focused on the cognitive processes involved in deriving the meaning of things motivating behaviour (Blumer, 1986). Such an approach provided limited insight into the motives and outcomes produced during interaction. In contrast, Social Exchange Theory articulated the utilitarian function of social relations and their contingency on other actors. It paved the way towards understanding the rational mechanisms underpinning decision making and the perception of the outcomes of social exchange (Heath, 1976).

Theory

Social Exchange Theory explains four main constituents of the social behaviour of individuals. First, the framework defines reinforcement tools – i.e. the rewards/benefits and resources of exchange - underpinning individuals’ motivation to engage in social interaction. A reward is an outcome of relations having a positive connotation, while a resource is an attribute giving a person a capability to enable the reward, stimulating people to embark on exchange relations (Emerson, 1976). Resources can represent love, status, money, information, services and goods (Foa & Foa, 1980). The associated rewards for exchanged resources can be allocated along a two-dimensional matrix. The first dimension is particularism, which indicates that the worth of exchanged resources depends on the source. For instance, a monetary resource is evaluated as low at the particularism scale, as regardless of the source the value of the money is the same. In contrast, love has a high particularism score, as the value of this resource is strongly associated with the provider. The second dimension of resources refers to concreteness, which is the degree of the resource’s tangibility. The resources which have low concrete value could be regarded as symbolic and have more value for receiving parties (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Overall, resources enable two types of rewards: socioemotional and economic benefits. The socioemotional benefits result from situations when acquired resources increase self-esteem and tackle social needs, while the economic benefits address financial needs (Shore et al., 2006). However, there is no consistency in the findings of prior research as to whether both types of benefits are equally important for the parties in relations (Chen, 1995; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005).

The second constituent refers to the mechanisms of exchange. The theory postulates that resources are exchanged based on the subjective cost-reward analysis (Blau, 2017; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Such an analysis is contingent on two main conditions defining the decision of the person to perform exchange relations. These conditions are: a) the degree to which a similar performance has been rewarded to a person or other people in the past and b) the degree to which the result of the exchange is valuable to a person (Blau, 2017; Homans, 1961). This is generally attributed to Homans’s views that the more often individuals receive a reward for an action, the more likely they will engage in future actions under similar conditions (Homans, 1961). Cost and benefit factors in the social exchange are different from the economic exchange, as the conditions and obligations are not clearly specified (Blau, 2017). Therefore, the evaluation of the fairness of the costs invested in relations and the rewards resulting from them is subjective. The perception is dependent on individual norms of fairness and as a result it should be interpreted from the user's perspective (Homans, 1961; Blau, 2017). To understand a user’s perception, it is important to understand differences among people, in terms of exchange orientation, the differences in the comparison of costs and rewards over time and the difference of contexts (Varey, 2015).

Third, social exchange relations are stimulated by social structures and social capital factors (Blau, 2017; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Samuel, 1994). The dependence on social structures reflects the contingency of the outcome of interactions on the initial relationship between the parties (Blau, 2017; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Social capital represents different forms of social entities, including norms, rules, information channels, expectations and obligations. These entities are embedded in the structures of social organisations. Social capital can not only facilitate, but also restrict the development of social relations and their outcomes (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998; Wasko & Faraj, 2005; Samuel, 1994). The outcomes may include power and equity distribution within social networks. Thus, the structural relation between the actors of the sharing economy platform reflects the number of valued resources that the actors control and the balance of resource distribution against other actors (Samuel, 1994). For example, it was found that organisational social capital, reflecting the collective commitment and self-sacrifice of the leadership, contributes to cooperative behaviour and undermines opportunistic behaviours (Mostafa & Bottomley, 2020). Social capital was examined not only as a factor facilitating the cooperation between people, but as a reward of relations. It was found that interpersonal interactions are driven by the expected maximisation of social benefits, such as enhanced social ties and networks (Wang & Liu, 2019).

The fourth mechanism underpinning social exchange is reciprocity, which creates obligations between the parties (Molm, 1997; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Emerson, 1976). The explanaiton of the role of reciprocity in social exhcnage and interdependence between social actors stems from research on experimental economics and evolutionary psychology, postulating that humans are evolutionarily predisposed to behave in such a way as to ensure reciprocation (DeLamater & Ward, 2013; Thibaut & Kelley, 2017; Hoffman, McCabe & Smith, 1998). People have developed mental matrices on the balance of rewards-costs in relations that underpin decision making (Hoffman, McCabe & Smith, 1998). On the one hand, reciprocity represents the norm defining beliefs about the outcome of exchange and motivating behaviour. People embark on relations with an expectation that the favour (i.e. contributions to relations) will be returned, though without the requirement to do it immediately. The lack of a specific time-frame of the return of favour makes social exchange long-term oriented (Molm, 1997). This expectation can be rooted in cultural norms or individual moral orientation revolving around the beliefs that the parties will reach a fair agreement, in which unfair treatment by a party will be punished, while fair treatment will be rewarded (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). On the other hand, the rule of reciprocity acts as a regulating mechanism, ensuring mutually rewarding relationships based on actors’ interdependence (Blau, 2017; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Interdependence is manifested as mutual and complementary arrangements, motivating the other party to pay back for the resource provided (J., 1969; Molm, 2003). Although exchange based on negotiated rules (as in economic transactions) is more straightforward, social exchange based on the reciprocity rule results in the more long term and reliable relations through the development of trust, loyalty and mutual commitment (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Molm, Peterson & Takahashi, 1999).

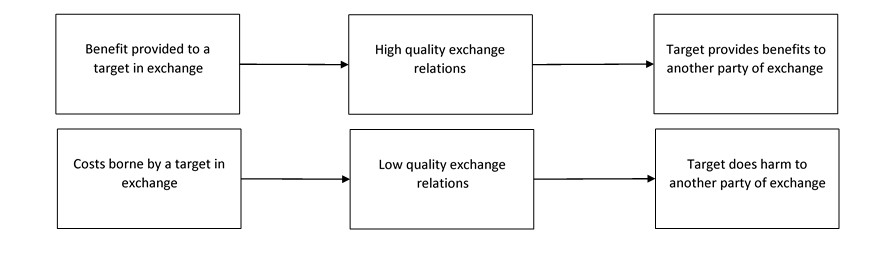

Given the above, the process of social exchange can be presented as a two-step behavioural model (Figure 1). The social exchange is initiated from the positive or negative treatment of the target of exchange (Cropanzano et al., 2017). A positive action is rewarding for the target and can represent the provision of support, high-quality service or goods (Riggle, Edmondson & Hansen, 2009; Cropanzano, 2003). A negative action can represent the sacrifices that the target bears, such as abuse, selfishness or bullying (Tepper et al., 2009; Rayner & Keashly, 2005). In response to such actions, the target actor reciprocates with good or bad behaviour to achieve equity, whereby good behaviour is reciprocated with a good deed, and negative behaviour causes a negative response. A series of positive exchanges favouring both parties tends to translate into long-term cooperation and commitment (Cropanzano et al., 2017).

Extension

Affective Theory of Social Exchange

Due to the economic principle of cost-benefit analysis in social exchange, SET views motives, perceptions and outcomes of social behaviour as rational and actors of exchange as emotionless. While the theory claims that social relations are sustained due to rational choices and reinforcement mechanisms, it does not consider the mediating role of emotions that are intertwined in those mechanisms (Lawler, 2001). Emotions are positive and negative states with neurological and cognitive properties. Although Homans (1961), Blau (1964) and Thibaut and Kelley (1959) admitted the role of emotions in certain aspects of behaviour evaluation (e.g. sentiment, intrinsic perception and the comparison level), they did not theorise about these aspects (Blau, 2017; Homans, 1961; Thibaut & Kelley, 2017).

To bridge the gap in the literature, Lawler (2001) developed the Affective Theory of Social Exchange (Lawler, 2001). The theory draws on a review of the literature on emotions and their implications for the contexts, processes and outcomes of exchange (Izard, 1991; Izard, 1991). The review enabled Lawler (2001) to distinguish global and specific emotions from sentiments. Emotions refer to an internal state that can be attached to an ambiguous source (global emotions) or attached to a specific event or object (specific emotions). Sentiments refer to an enduring affective state in relation to the social context or object(s). Global emotions potentially transition to specific emotions and sentiments. The goal of the theory was to understand the conditions in which social exchange leads social actors towards attaching global negative and positive emotions (i.e. feeling good and feeling bad) to social objects and develop enduring negative and positive feelings to them (Lawler, 2001).

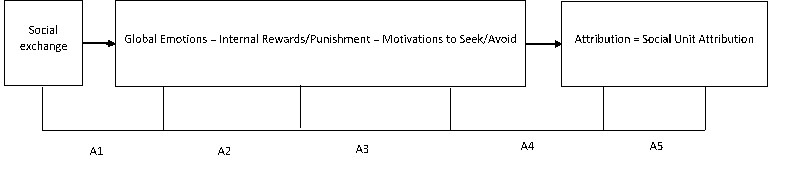

Building on the prior research on commitment in social relations (Lawler & Thye, 1999; Lawler, 2001), five theoretical assumptions were developed (Fig 2). The fundamental argument of these assumptions is that positive emotions produced as a result of exchange create solidarity effects, manifested through expanding collaborations, non-obligated exchange of benefits, loyalty and forgiving behaviour (Lawler & Yoon, 1996; Lawler & Thye, 1999; Lawler, 2001). A social exchange was assumed to produce positive and negative global emotions depending on the outcomes of the exchange (assumption 1). These emotions serve as a distinctive type of rewards and punishments (assumption 2). An exchange can motivate actors to carry out or refrain from the exchange, as a way to reproduce positive emotions (e.g. pride in self and gratitude toward the other) and prevent negative ones (e.g. shame in self, anger towards the other) (assumption 3) (Lawler, 2001).

Affective states motivate actors to invest cognitive effort in understanding the sources of emotions (assumption 4) (Lawler, 2001). Global emotions can trigger an attribution process. Attribution is the process of associating emotions with more specific, object-focused emotions (Sorrentino & Higgins, 1986). Objects include task, self, other, relationships and social groups. Tasks are embedded in exchange structures, which can be productive, negotiated, reciprocal and generalised. Task properties, defined as the degree to which actors’ contributions to tasks are separable from the contributions of other people and the degree to which actors share responsibility for the task, refer to the type of exchange structure. Productive exchange pursues the generation of a joint good. Negotiated exchange is carried out under predefined terms and conditions. Reciprocal exchange implies reciprocation without a strict timeframe and conditions. Generalised exchange means that reciprocation is carried out indirectly to a member of the group, other than the one who initially provided resources (Molm, 1994; Howard & Ekeh, 1976). The varying degree of shared responsibility and task separability across the types of exchange structures determine the strength of pleasant and unpleasant feelings. Feelings trigger the emotional attribution of the task success and failure to the self and/or other people involved in the exchange, thus inducing associated object-specific emotions (e.g. pride in oneself, gratitude to others) (Lawler, 2001).

The fifth assumption states that the explanation of the source of global emotions by actors is carried out with reference to social objects, such as people, social relations, events or social networks. That means that emotional attribution results in either affective attachment (association of emotions) or detachment (disassociation of emotions) from objects. Affective attachment occurs in conditions when social objects represent controllable and stable causes of positive emotions. Negative emotions caused by social objects representing stable and uncontrollable causes result in effective detachment (Lawler, 2001). In the context of education, a stable controllable cause can be a personal skill and capability, while a stable uncontrollable cause can be represented by the difficulty of the tasks provided by a teacher (Kelley & Michela, 1980). The theoretical assumptions of the Affective Theory of Social Exchange provide a detailed account of the conditions under which particular types of emotions are manifested and their role in regulating the evaluation process of social exchange outcomes. The theory does not dispute the rational premises of social exchange, but rather complements Social Exchange Theory with the theorisation of the non-rational aspect of behaviou which is inherent to humans. The theory explains the ways through which rational choices are interrelated with affective states, thus providing implications for the development of solidarity and sustained relations.

Applications

Social exchange theory is a very broad framework, fitting many micro and macro-sociological theories. The rather generic conceptualisation of relations within communities enables the theory to explain almost any reasonable finding about the pattern of behaviour (Cropanzano et al., 2017). The focus on the ubiquitous principle of reciprocity persistent in social relations makes the theory the pillar of social behaviourism (DeLamater & Ward, 2013). It has become the unitary framework explaining social power (Molm, Peterson & Takahashi, 1999), networks (Tsai & Cheng, 2012), justice (Ambrose & Schminke, 2003), psychological contracts (Rousseau, 1995) and other social phenomena. The principles of the theory have driven a large body of research attempting to describe and explain different aspects of individuals’ behaviour, manifested in various disciplinary contexts.

The research on individuals’ behaviour takes three directions. First, the theory was used to explore the cost-benefit evaluation that predefines individuals’ decisions to participate in social activities (Kankanhalli, Tan & Wei, 2005; Kanwal et al., 2020). The focus on costs and benefits was conducive to contexts where relations take place (Kankanhalli, Tan & Wei, 2005; Kanwal et al., 2020). For example, in a study exploring the response of the community to infrastructural development, perceived negative impact and perceived benefits of interventions were examined in relation to satisfaction with and support for those interventions. The results of the study showed that the outcome of behaviour can be predicted by a negative correlation with perceived negative impact and a positive correlation with perceived benefits (Kanwal et al., 2020). Another piece of research focused on the role of actual and potential costs against the extrinsic and intrinsic benefits of sharing activities in organisations. The sharing practice was proved to be the result of the compromise between the input of effort to perform the practice, the obligation to reciprocate, organisational rewards (e.g. salary increase, incentives, job security), altruistic benefit (helping others) and perceived confidence about the positive outcome of the practice (Kankanhalli, Tan & Wei, 2005). Also, researchers weighted the costs and benefits of practices to evaluate the expected reciprocity of relations (Kankanhalli, Tan & Wei, 2005; Kanwal et al., 2020). They have also tested the reciprocity norm as a belief in fair exchange (Davlembayeva, Papagiannidis & Alamanos, 2020). A great deal of empirical evidence has provided support for the principle of the theory that the expectation of reciprocity drives individuals’ engagement in relations (Molm, 1997; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). A belief in reciprocal relations is associated with satisfaction, motivating continuous behaviour (Shiau & Luo, 2012). It is the strongest social factor predicting users’ intention to participate in the sharing economy (Davlembayeva, Papagiannidis & Alamanos, 2020) and the antecedent of helping behaviour in organisations (Thomas & Rose, 2010).

The second body of research focused on the outcomes of reciprocal and non-reciprocal exchange. Reciprocal relations result in commitment, satisfaction and other manifestations of a positive behaviour (Griffin & Hepburn, 2005). Researchers concluded that reciprocity has a mediating effect on commitment through trust (Coyle-Shapiro et al., 2002), as well as a direct effect on commitment demonstrated through emotional attachment (Griffin & Hepburn, 2005). When it comes to non-reciprocal relations, scholars have argued that perceived negative inequity (the perception that an individual received fewer rewards compared to costs) and positive inequity (the perception that the rewards are greater than the costs) leads to stress (Walster, Berscheid & Walster, 1973; Adams, 1963) and induces emotions like guilt and anger (Sherf & Venkataramani, 2015). The relations producing output that is discrepant from input trigger behaviours that aim to compensate or take revenge for the lack of reciprocation (Biron & De Reuver, 2013; Rosette & Zhou Koval, 2018). Pro-active behavioural measures to restore inequity include physical compensation for inequity (increase rewards to another party), self-deprivation (decrease reward to oneself to equate with the reward of another party) and retaliation against the party of relations causing inequity (Walster, Berscheid & Walster, 1973; Folkman & Lazarus, 1988). Cognitive processes such as self-affirmation, denial of responsibility and the devaluation of the input of the other party of relations refer to the emotion-focused measures of inequity restoration (Walster, Berscheid & Walster, 1973; Davies et al., 2018). Self-affirmation is the persuasion of oneself that relationships are equitable. Devaluation of the input of the other party and denial of responsibility concern the refusal to accept the blame for the inequitable treatment of another party by psychologically distorting his/her inputs and outcomes, decreasing or increasing them as required (Walster, Berscheid & Walster, 1973).

The third stream of research used the SET framework to study social capital factors in the formation of dyadic and collective relations (Davlembayeva, Papagiannidis & Alamanos, 2020; Koopman et al., 2015). Factors such as trust, social norms, altruism or egoistic motives affect the evaluation of the outcome of relations (Reiche, 2012; Davlembayeva, Papagiannidis & Alamanos, 2020; Koopman et al., 2015). For example, there is evidence that trust and ties are the predictors of continuous knowledge sharing (Reiche, 2012). Social capital produced through the ingratiation towards superior group members positively contributes to the quality of exchange relations (Koopman et al., 2015). In the context of the sharing economy, individuals’ participation in sharing platforms is conditioned by the positive effect of egoistic belief, reciprocity norm and social value (Davlembayeva, Papagiannidis & Alamanos, 2020). Although the findings have not been consistent in terms of the significance of specific social capital factors, the overall proposition of Social Exchange Theory about the facilitating and inhibiting role of social capital has largely been confirmed across studies.

As far as the context is concerned, a large amount of evidence exists about the employment of Social Exchange Theory to investigate the behaviour of people in the organisational context (Long, Li & Ning, 2015; Slack, Corlett & Morris, 2015). The theory explained the volition of employees towards engagement with corporate social responsibility activities (Slack, Corlett & Morris, 2015) and the motivation to engage in extra-role performance as a payback for the positive environment created in the organisation (Long, Li & Ning, 2015). The Social Exchange Framework is an influential tool in explaining relationship models functioning on the basis of information systems (Shiau & Luo, 2012; Baxter & Braithwaite, 2008). In the information systems management discipline, the theory was used to explore the effect of different constructs related to costs and rewards on the exchange practices in online communities (Geiger, Horbel & Germelmann, 2018; Kankanhalli, Tan & Wei, 2005) and technology utilisation and acceptance (Gefen & Keil, 1998). For example, it was helpful in identifying the risks and benefits of using online-based knowledge management systems, which has contributed to the utilisation of the system for sharing knowledge among system members (Kankanhalli, Tan & Wei, 2005). The theory, combined with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, has been used as an overarching theoretical model to explain the determinants of knowledge sharing on websites. The empirical testing of the model showed that perceived benefits trigger general and specific knowledge sharing behaviour, while the associated costs (e.g. cognitive and execution costs) inhibit that behavioural intention (Yan et al., 2016). The application of the theory to studying the rationale for engagement in online social networking websites suggests that the opportunity to strengthen social ties and control privacy are considered against the privacy risks entailed by using social media tools (Wang & Liu, 2019). In the area of medicine, the theory has guided studies exploring the utilisation of mobile health-based interventions designed to propose medication adherence among patients. The findings of those studies showed that negative and positive reinforcement (i.e. cost and rewards) encourage or discourage the use of the system (Chatterjee, 2019). Also, research on entrepreneurship confirmed that the cost-reward evaluation is the mechanism underpinning entrepreneurs’ decision making. Specifically, investment decisions are determined by the beliefs that project costs should not exceed the promised benefits (Zhao et al., 2017).

Limitations

The principles that ensure the wide application of Social Exchange Theory have come to face criticism (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Coyle-Shapiro et al., 2002). It has been argued that the core ideas of the theory are not adequately articulated and integrated, which creates problems when using them as an overarching framework in research. The major limitation concerns the non-exhaustive and overlapping list of constructs, which limit the explanatory capability of the theory and undermine its predictive power. The tendency to use an incomplete set of constructs leads towards a partial explanation of individuals’ behaviour. The vagueness of the theoretical principles results in a number of interpretations of their conceptual boundaries, which, in turn, creates a divergence in the interpretation of research findings (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). While the lack of precisely defined constructs makes the theory widely used across disciplines, it challenges the inference from conclusions and makes it difficult to replicate the findings (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005).

The second issue concerns a lack of accuracy and consistency in terminology. The original works by Blau (Blau, 2017) referred to social and economic exchanges as transactions and not relationships, like the mainstream literature (Organ, 1988). Despite attempts to clarify the difference between relationship and exchange, there is still a need to define whether an exchange is a type of relationship, a transaction that leads to a relationship or vice versa (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). For instance, a prior relationship between parties can have an effect on the exchange, and the exchange can contribute to the development of continued relationships. This debate has not been resolved to date, as scholars use the terms (transaction, relations) interchangeably (Mora Cortez & Johnston, 2020; Davlembayeva, Papagiannidis & Alamanos, 2020; Davlembayeva, Papagiannidis & Alamanos, 2021).

The third issue concerns the lack of consistency and definition of the rules of exchange across studies. Although the major principle of the theory is the rule of reciprocity, scholars adopt a number of other principles (e.g. negotiated rule, rationality, altruism, group gain, status consistency and competition) to explain behaviour (Gouldner, 1960; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Different rules of exchange create a heterogeneity of perspectives on individuals’ behaviour and put forward inconsistent findings (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Therefore, there is a need to have a clear and single definition for each rule of exchange to reduce the ambiguity associated with the theory's principles.

The fourth limitation concerns the operationalisation and the taxonomy of concepts. Although a vast number of empirical studies have measured the underpinnings and the outcomes of interpersonal relations (Davlembayeva, Papagiannidis & Alamanos, 2020; Long, Li & Ning, 2015; Koopman et al., 2015), the literature still represents a behaviour or social actors in too simplistic a way. Specifically, researchers differentiated the concept of positive and negative actions without a critical understanding of how the valence of action is defined (Cropanzano et al., 2017). As a result, the need to utilise broad standards for evaluating the deviance of behaviour that can be useful in determining the valence of social exchange constructs was questioned (Bennett et al., 2005). Another issue is the simplicity of presenting the structure of reciprocity. Reciprocity constructs fall into opposite categories – negative and positive. The logic behind this categorisation is that the absence of a positive event (e.g. supportive behaviour) equates to a negative event (e.g. abusive behaviour). However, this representation is unidimensional. It does not take into account the activity dimension, which can be used to differentiate actively exhibited positive/negative behaviour from withheld positive/negative behaviour (Cropanzano et al., 2017). Despite the conceptual difference between the types of behaviour, such a categorisation has not yet been empirically tested.

Concepts

| Concept | Definition | Reference | Measurements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | The alternative activities or opportunities foregone by the actors involved. | Homans, 1961 | N/A Independent |

| Equity | The balance between a person's inputs and outcomes on the job. | Adams, 1963 | Measurement Dependent |

| Norm of Reciprocity | The norm of reciprocity defines certain actions and obligations as repayments for benefits received. | Gouldner, 1960 | Measurement Independent |

| Reciprocity | The giving of benefits to another in return for benefits received, is one of the defining features of social exchange and, more broadly, of social life. | Molm, 2010 | Measurement Independent/Dependent |

| Reward | The sources of positive reinforcement. | Blau, 2017 | N/A Independent |

| Social Exchange | The exchange of activity, tangible or intangible, and more or less rewarding or costly, between at least two persons. | Homans, 1961 | N/A Dependent |

References

- Adams, J.S. (1963). Towards an understanding of inequity. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67 (5), 422-436.

- Ambrose, M.L. & Schminke, M. (2003). Organization structure as a moderator of the relationship between procedural justice, interactional justice, perceived organizational support, and supervisory trust. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88 (2), 295-305.

- Baxter, L.A. & Braithwaite, D.O. (2008). Engaging Theories in Interpersonal Communication. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Bennett, R.J., Aquino, K., Reed, A. & Thau, S. (2005). The Normative Nature of Employee Deviance and the Impact of Moral Identity. Counterproductive work behavior: Investigations of actors and targets., 107-125.

- Biron, M. & De Reuver, R. (2013). Restoring balance? Status inconsistency, absenteeism, and HRM practices. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22 (6), 683-696.

- Blau, P. (2017). Exchange and Power in Social Life. Routledge.

- Blumer, H. (1986). Symbolic Interactionism. University of California Press.

- Chatterjee, D.S. (2019). Explaining customer ratings and recommendations by combining qualitative and quantitative user generated contents. Decision Support Systems, 119, 14-22.

- Chen, C.C. (1995). New Trends in Rewards Allocation Preferences: A Sino-U.S. Comparison. Academy of Management Journal, 38 (2), 408-428.

- Coyle-Shapiro, J.A., Morrow, P.C., Richardson, R. & Dunn, S.R. (2002). Using profit sharing to enhance employee attitudes: A longitudinal examination of the effects on trust and commitment. Human Resource Management, 41 (4), 423-439.

- Cropanzano, R. & Mitchell, M.S. (2005). Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. Journal of Management, 31 (6), 874-900.

- Cropanzano, R. (2003). The Structure of Affect: Reconsidering the Relationship Between Negative and Positive Affectivity. Journal of Management, 29 (6), 831-857.

- Cropanzano, R., Anthony, E.L., Daniels, S.R. & Hall, A.V. (2017). Social Exchange Theory: A Critical Review with Theoretical Remedies. Academy of Management Annals, 11 (1), 479-516.

- Davies, S.G., McGregor, J., Pringle, J. & Giddings, L. (2018). Rationalizing pay inequity: women engineers, pervasive patriarchy and the neoliberal chimera. Journal of Gender Studies, 27 (6), 623-636.

- Davlembayeva, D., Papagiannidis, S. & Alamanos, E. (2020). Sharing economy: Studying the social and psychological factors and the outcomes of social exchange. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 158, 120143.

- Davlembayeva, D., Papagiannidis, S. & Alamanos, E. (2021). Sharing economy platforms: An equity theory perspective on reciprocity and commitment. Journal of Business Research, 127, 151-166.

- DeLamater, J. & Ward, A. (2013). Handbook of Social Psychology.

- Delamater, J. (2006). Handbook of Social Psychology (Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research). Springer.

- Emerson, R.M. (1976). Social Exchange Theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 2 (1), 335-362.

- Foa, E.B. & Foa, U.G. (1980). Resource Theory. Social Exchange, 77-94.

- Folkman, S. & Lazarus, R.S. (1988). Coping as a mediator of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54 (3), 466-475.

- Gefen, D. & Keil, M. (1998). The impact of developer responsiveness on perceptions of usefulness and ease of use. ACM SIGMIS Database: the DATABASE for Advances in Information Systems, 29 (2), 35-49.

- Geiger, A., Horbel, C. & Germelmann, C.C. (2018). “Give and take”: how notions of sharing and context determine free peer-to-peer accommodation decisions. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 35 (1), 5-15.

- Gouldner, A.W. (1960). The Norm of Reciprocity: A Preliminary Statement. American Sociological Review, 25 (2), 161.

- Griffin, M.L. & Hepburn, J.R. (2005). Side-bets and reciprocity as determinants of organizational commitment among correctional officers. Journal of Criminal Justice, 33 (6), 611-625.

- Heath, A.F. (1976). Rational choice & social exchange. Cambridge University Press.

- Hoffman, E., McCabe, K. & Smith, V. (1998). BEHAVIORAL FOUNDATIONS OF RECIPROCITY: EXPERIMENTAL ECONOMICS AND EVOLUTIONARY PSYCHOLOGY. Economic Inquiry, 36 (3), 335-352.

- Homans, G.C. (1961). Social behavior.

- Howard, L. & Ekeh, P.P. (1976). Social Exchange Theory: The Two Traditions. Contemporary Sociology, 5 (5), 665.

- Izard, C.E. (1991). The psychology of emotions. Plenum Press.

- J., G.K. (1969). Psychology of Behaviour Exchange (Topics in Social Psychology). Longman Higher Education.

- Kankanhalli, Tan, & Wei (2005). Contributing Knowledge to Electronic Knowledge Repositories: An Empirical Investigation. MIS Quarterly, 29 (1), 113.

- Kanwal, S., Rasheed, M.I., Pitafi, A.H., Pitafi, A. & Ren, M. (2020). Road and transport infrastructure development and community support for tourism: The role of perceived benefits, and community satisfaction. Tourism Management, 77, 104014.

- Kelley, H.H. & Michela, J.L. (1980). Attribution Theory and Research. Annual Review of Psychology, 31 (1), 457-501.

- Knight, M.M. (1940). HERSKOVITS, MELVILLE J. The Economic Life of Primitive Peoples. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 210 (1), 184-185.

- Koopman, J., Matta, F.K., Scott, B.A. & Conlon, D.E. (2015). Ingratiation and popularity as antecedents of justice: A social exchange and social capital perspective. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 131, 132-148.

- Lawler, E.J. & Thye, S.R. (1999). BRINGING EMOTIONS INTO SOCIAL EXCHANGE THEORY. Annual Review of Sociology, 25 (1), 217-244.

- Lawler, E.J. & Yoon, J. (1996). Commitment in Exchange Relations: Test of a Theory of Relational Cohesion. American Sociological Review, 61 (1), 89.

- Lawler, E.J. (2001). An Affect Theory of Social Exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 107 (2), 321-352.

- Long, C., Li, Z. & Ning, Z. (2015). Exploring the nonlinear relationship between challenge stressors and employee voice: The effects of leader–member exchange and organisation-based self-esteem. Personality and Individual Differences, 83, 24-30.

- Malinowski (2013). Man and Culture. Routledge.

- Molm, L.D. (1994). Dependence and Risk: Transforming the Structure of Social Exchange. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57 (3), 163.

- Molm, L.D. (1997). Coercive power in social exchange. Cambridge University Press.

- Molm, L.D. (2003). Theoretical Comparisons of Forms of Exchange. Sociological Theory, 21 (1), 1-17.

- Molm, L.D., Peterson, G. & Takahashi, N. (1999). Power in Negotiated and Reciprocal Exchange. American Sociological Review, 64 (6), 876.

- Mora Cortez, R. & Johnston, W.J. (2020). The Coronavirus crisis in B2B settings: Crisis uniqueness and managerial implications based on social exchange theory. Industrial Marketing Management, 88, 125-135.

- Mostafa, A.M.S. & Bottomley, P.A. (2020). Self-Sacrificial Leadership and Employee Behaviours: An Examination of the Role of Organizational Social Capital. Journal of Business Ethics, 161 (3), 641-652.

- Nahapiet, J. & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23 (2), 242-266.

- Organ, D.W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior. Lexington Books.

- Rayner, C. & Keashly, L. (2005). Bullying at Work: A Perspective From Britain and North America. Counterproductive work behavior: Investigations of actors and targets., 271-296.

- Reiche, B.S. (2012). Knowledge Benefits of Social Capital upon Repatriation: A Longitudinal Study of International Assignees. Journal of Management Studies, 49 (6), 1052-1077.

- Riggle, R.J., Edmondson, D.R. & Hansen, J.D. (2009). A meta-analysis of the relationship between perceived organizational support and job outcomes: 20 years of research. Journal of Business Research, 62 (10), 1027-1030.

- Rosette, A.S. & Zhou Koval, C. (2018). Framing advantageous inequity with a focus on others: A catalyst for equity restoration. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76, 283-289.

- Rousseau, D.M. (1995). Psychological contracts in organizations. SAGE Publications.

- Samuel, C.J. (1994). Foundations of social theory. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Sherf, E.N. & Venkataramani, V. (2015). Friend or foe? The impact of relational ties with comparison others on outcome fairness and satisfaction judgments. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 128, 1-14.

- Shiau, W. & Luo, M.M. (2012). Factors affecting online group buying intention and satisfaction: A social exchange theory perspective. Computers in Human Behavior, 28 (6), 2431-2444.

- Shore, L.M., Tetrick, L.E., Lynch, P. & Barksdale, K. (2006). Social and Economic Exchange: Construct Development and Validation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36 (4), 837-867.

- Slack, R.E., Corlett, S. & Morris, R. (2015). Exploring Employee Engagement with (Corporate) Social Responsibility: A Social Exchange Perspective on Organisational Participation. Journal of Business Ethics, 127 (3), 537-548.

- Sorrentino, R.M. & Higgins, E.T. (1986). Handbook of motivation and cognition. Guilford Press.

- Tepper, B.J., Carr, J.C., Breaux, D.M., Geider, S., Hu, C. & Hua, W. (2009). Abusive supervision, intentions to quit, and employees’ workplace deviance: A power/dependence analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 109 (2), 156-167.

- Thibaut, J.W. & Kelley, H.H. (2017). The Social Psychology of Groups. Routledge.

- Thomas, C. & Rose, J. (2010). The Relationship between Reciprocity and the Emotional and Behavioural Responses of Staff. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 23 (2), 167-178.

- Tsai, M. & Cheng, N. (2012). Understanding knowledge sharing between IT professionals – an integration of social cognitive and social exchange theory. Behaviour & Information Technology, 31 (11), 1069-1080.

- Varey, R.J. (2015). Social Exchange (Theory). Wiley Encyclopedia of Management, 1-3.

- Walster, E., Berscheid, E. & Walster, G.W. (1973). New directions in equity research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 25 (2), 151-176.

- Wang, X. & Liu, Z. (2019). Online engagement in social media: A cross-cultural comparison. Computers in Human Behavior, 97, 137-150.

- Wasko, & Faraj (2005). Why Should I Share? Examining Social Capital and Knowledge Contribution in Electronic Networks of Practice. MIS Quarterly, 29 (1), 35.

- Yan, Z., Wang, T., Chen, Y. & Zhang, H. (2016). Knowledge sharing in online health communities: A social exchange theory perspective. Information & Management, 53 (5), 643-653.

- Zhao, Q., Chen, C., Wang, J. & Chen, P. (2017). Determinants of backers’ funding intention in crowdfunding: Social exchange theory and regulatory focus. Telematics and Informatics, 34 (1), 370-384.

Video

Click to subscribe to our YouTube Channel.

Study in the UK

Authors

Dinara Davlembayeva (Business School, Cardiff University, UK) & Eleftherios Alamanos (Business School, Newcastle University, UK)

Feedback: Email the corresponding author ()

How to Cite

Davlembayeva, D.& Alamanos, E. (2023) Social Exchange Theory: A review. In S. Papagiannidis (Ed), TheoryHub Book. Available at https://open.ncl.ac.uk / ISBN: 9781739604400

Last updated

2023-09-25 14:32:03

Licence

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Theory Profile

Proposed by

Homans, 1961

Related Theories

Social Comparison Theory, Social Capital Theory, An Affective Theory of Social Exchange, Rational Choice Theory

Discipline

Sociology

Unit of Analysis

Social Groups, Dyadic relations

Operationalised

Qualitatively / Quantitatively

Level

Meso-level

Type

Theory for Explaining and Predicting

YouTube

Video